A short view of land restoration in the central Texas hill country. Restoration there turned an overgrazed, dry, and dusty ranch into a forest with lakes, fresh springs, and wildlife.

Jump to: Films | Podcasts | Articles | Books | Lessons

Films

50 Years Ago, This Was A Wasteland

Categories: Ecology, Humans & Nature, Short Films

Vandana Shiva on Sustainability

Categories: Climate Change, Culture, Decolonization, Humans & Nature, TED Talks, Top Picks

“Whatever I do, I do from a deep love… a very deep love for life and all its gifts and bounties. And it’s that love that replenishes me and recharges me to go on. I’m not doing a job for anybody. Nobody is paying me a salary—this much nine-to-five and a little bonus if you do more. No, this is about living. It is about the joy of living. And if that joy of living requires that those who are robbing the planet of its life, those who are robbing people of their lives have to be resisted and questioned, I will do that too. That too is part of my resistance.”

Let’s Not Use Mars As A Backup Planet

Categories: Climate Change, Humans & Nature, TED Talks

Among young people, ideas like colonizing Mars are enticing. Lucinanne Walkowicz urges us to reconsider notions that we could escape environmental crisis on Earth. Even the most inhospitable deserts and ice caps on Earth are still more habitable than Mars.

The Shocking Move to Criminalize Nonviolent Protest

Categories: Culture, Humans & Nature, TED Talks

The author of Green is the New Red looks into the wealth and power behind environmental politics.

Plant Some Trees Right Where You Are

Categories: Culture, Humans & Nature, TED Talks

How can one person make a difference in the world? As a wise man told Por Phonamnuai, plant some trees right where you are. So he transformed his urban environment of Chiang Mai, Thailand by planting thousands of trees—fighting the growing urban heat bubble, creating a sense of civic engagement, and getting ordinary people to take ownership for the environment they live in.

Life is Easy—Why Do We Make It So Hard?

Categories: Culture, Humans & Nature, TED Talks, Top Picks

In great eloquence, our friend P’Jo (Jon Jondai) lays out his philosophy for life and his simple, undeniable refutation of the superiority of modern “culture.” The most important parts of life are easy when you have a group of friends and family doing them with you, and the Earth provides for us. Our modern lives seem crazy when compared to nature: a bird builds her nest in two days yet we work in uncomfortable, stressful jobs for 30 years to pay for ours. It might take a little longer than two days to build a house, but P’Jo offers solutions at Pun Pun Farm that are viable alternatives to the path we are on.

The True Cost of Oil

Categories: Energy, Humans & Nature, TED Talks, Transportation

Photographer Garth Lenz uses his images of beauty and devastation to take us inside the most damaging fossil fuel extraction operation on Earth: mining in the Alberta Tar Sands. The tar sands represent a net loss of energy. With high oil prices though, it’s profitable to burn more oil than you produce, pollute the land and water, and call it job creation.

How I Fell In Love With A Fish

Categories: Food, Humans & Nature, TED Talks

Chef Dan Barber takes us into his search for an answer to a big question: in an era of fishery collapse, how can he serve fish on his menu without causing harm to the world. His journey to Spain is inspiring, going beyond the question of sustainable fisheries and into our basic assumptions about food production and our relationship with the natural world.

Free the Snake: Restoring America’s Greatest Salmon River

Categories: Humans & Nature, Short Films, Water

Pacific salmon swim up rivers from the ocean in order to spawn, returning to the exact same stream they originated from. In the Snake River watershed, salmon used to reach central Idaho and Wyoming. With the removal of 4 dams produce minimal electricity, over 500 miles of salmon river habitat could be restored.

Grief and Praise

Categories: Culture, Humans & Nature, TED Talks

Martín Prechtel shares his spiritual perspective on the interconnected web of problems facing the world today. This is part 1 of a 3-part talk—we trust you can find the rest on youtube.

The Man Who Planted Trees (1987)

Categories: Culture, Ecology, Humans & Nature, Top Picks

The Man who Planted Trees is an award-winning animated short film based on a short story by the same title. In brief, the film tells the story of a shepherd—Elzéard Bouffier’s—attempt to re-forest an entire French valley alone, becoming acquainted with values of love, compassion and peace that the practice brings him through the years. Accompanied by whimsical illustrations and a touching storyline, this film highlights the tranquility and compassion that often get overshadowed in stories of modern-day environmentalism.

SEED: The Untold Story

Categories: Food, Humans & Nature, Top Picks

“We lost 94 percent of our vegetable seed varieties in the 20th century,” the film informs the viewer. This visually stunning film chronicles the movement to protect seeds—a practice called “seed saving”—before many disappear forever. Warning of the grave danger seeds are in, this film urges the viewer to recognize our irreparable destruction of ancient seeds, the vulnerability of seeds, and forces them to acknowledge what’s at stake for the future of mankind.

A Fierce Green Fire

Categories: Climate Change, Culture, Humans & Nature, Top Picks

This documentary guides viewers through the history of environmentalism through an empowering lens of collaboration, cooperation, and success in unlikely fights. Taking a look at the environmental movement’s connection to matters of water pollution, toxic waste, climate change, whaling, and damming—just to name a few—A Fierce Green Fire reminds us of the passion that comprises the foundation of the environmental movement.

If a Tree Falls: A Story of the Earth Liberation Front

Categories: Environmental Justice, Humans & Nature

“When you’re screaming at the top of your lungs and nobody hears you, what are you supposed to do?”. Tired of the wealthy few destroying the environment for profit, members of the Earth Liberation Front in the Pacific Northwest developed a militant wing to try and get their message heard. Inspired by Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang, these controversial “eco-terrorists” took on new means of trying to defend the world they loved. The film challenges the viewer’s perception of environmental activism and the fight to preserve our land.

DamNation

Categories: Humans & Nature, Top Picks, Water

Controversy over dams is emotional and heated. Surging rivers are powerful symbols of the wild and central components in their ecosystems. To most environmentalists, dams are the quintessential representation of destroying something wild to promote something artificial, whether it’s irrigating the desert or shipping material goods up rivers. After a century of excessive dam building, the tide is turning and dam removal has begun. DamNation is a visual narrative of the previous, guiding the viewer through the history, social and environmental implications of damming and dam removal.

The City Dark

Categories: Culture, Humans & Nature

For many, seeing a truly dark night sky is a humbling experience that is becoming rare in modern America. Filmmaker Ian Cheney asks “what do we lose, when we lose the dark?,” as he explores the relationship between humans, stars, artificial light and darkness throughout the United States. This documentary offers an in-depth look at the ramifications of artificial light and light pollution in our world.

The Important Places

Categories: Humans & Nature, Short Films

In this ten minute short film, filmmaker and adventure photographer Forest Woodward tells a story of his father’s relationship with the Colorado River, stressing the strong connection between humans and wild spaces. The film, supported by the river advocacy organization American River, reminds the viewer of the importance of protecting our wild spaces. The Important Places is a touching, feel-good film about family and the places we deem sacred, portraying American land conservation through an emotionally evocative lens.

Canyon Song

Categories: Culture, Humans & Nature, Short Films

This short film introduces viewers to the Draper family, a Navajo family descending from participants of the “Long Walk”—a systematic forcing of Navajo people off their land by US military in 1864—as they stay connected to their ancestral lands of Canyon de Chelly National Monument. Two young girls, Tonisha and Tonielle Draper, live typical “American lives” on the surface, but are active in the reclamation of their Navajo heritage, reconnecting with ancestors, and showing deep reverence to the land within the canyon walls. Though an uplifting, hopeful film about connection, Canyon Song urges viewers to acknowledge the ability of natural spaces to serve as powerful reminders of history and culture—and necessitates their preservation through its implication of the preservation of an entire community’s tradition.

Holy (un)Holy River

Categories: Culture, Humans & Nature, Short Films

Follow two filmmakers down India’s most sacred river—the Ganges, termed “Ma Ganga,” or “Mother Ganges” by many Hindus. Seen as a source of life, the river is a sacred body that flows 1,569 miles through the subcontinent. But it’s purity is threatened by increasing industrial emissions, damming, household trash, human remains, and sewage, all of which are exacerbated by unhindered population growth. “But if we worship it, how can we defile it?,” one woman in the film asks, calling attention to the contradiction of the world’s most holy river being threatened by the byproducts of a rapidly industrializing world. Holy (un)Holy River prompts the viewer question to question: how can a so-called ‘source of life’ put the lives of anyone bathing or drinking it at risk? Where can restoring the life of the Ganges begin?

The Memory of Fish

Categories: Food, Humans & Nature, Short Films, Water

This film introduces the viewer to Dick Goin, a vibrant aging man with a deep reverence for the Elwha River on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula—a body of water that him and his family have personally and professionally relied on since the 1930s. With the river’s salmon population steadily decreasing due to damming, Goin fights to bring back the salmon. Ultimately, The Memory of Fish demonstrates the direct threat being placed on individuals as a result of widespread habitat destruction that stems from modern policy as Goin aims to bring life back to the river that has, in many ways, sustained his own life.

180° South: Conquerors of the Useless

Categories: Culture, Ecology, Humans & Nature

This documentary is the quintessential adventure classic. Splitting time between wild places and the developing world of South America, this film delves into the mindset of living for the journey, not the destination. Along the way, the hero explores sustainability in the developing world, collapse of past civilizations, and some of the largest and most innovative conservation efforts on the continent.

Articles

Soil as Carbon Storehouse: New Weapon in Climate Fight?

Categories: Climate Change, Ecology, Humans & Nature

The damage or disappearance of ecologies and plant cover have caused significant soil degradation, which, it turns out, has released much CO2 into the atmosphere. In fact, the world’s cultivated soils have lost between 50 and 70 percent of their original carbon stock, according to recent research, much of which has oxidized upon exposure to air to become CO2. But new research is finding ways to recapture CO2 through land restoration.

“Recognition of the vital role played by soil carbon could mark an important if subtle shift in the discussion about global warming, which has been heavily focused on curbing emissions of fossil fuels. But a look at soil brings a sharper focus on potential carbon sinks. Reducing emissions is crucial, but soil carbon sequestration needs to be part of the picture as well, says Lal. The top priorities, he says, are restoring degraded and eroded lands, as well as avoiding deforestation and the farming of peatlands, which are a major reservoir of carbon and are easily decomposed upon drainage and cultivation.

Goreau says we need to seek opportunities to increase soil carbon in all ecosystems — from tropical forests to pasture to wetlands — by replanting degraded areas, increased mulching of biomass instead of burning, large-scale use of biochar, improved pasture management, effective erosion control, and restoration of mangroves, salt marshes, and sea grasses.

Scientists say that more carbon resides in soil than in the atmosphere and all plant life combined; there are 2,500 billion tons of carbon in soil, compared with 800 billion tons in the atmosphere and 560 billion tons in plant and animal life. And compared to many proposed geoengineering fixes, storing carbon in soil is simple: It’s a matter of returning carbon where it belongs.”

How Big Business Is Hedging Against the Apocalypse

Categories: Climate Change, Economics, Energy, Humans & Nature

Investors are finally paying attention to climate change — though not in the way you might hope.

Global energy consumption is rocketing upward every year: The Energy Information Administration expects it to climb another 28 percent within a generation. Hydropower, wind and solar contribute about 22 percent of the total, and their share grows yearly. But the net amount of energy generated by hydrocarbons is growing yearly, too.

Unlike almost every other future event, climate change is 100 percent certain to happen. What we don’t know is everything else: where, or how, or when, or what the changes mean for Facebook or Pfizer or notes of Chinese-government debt. Navigating these thickets of complexity is theoretically what Wall Street excels at; the industry prides itself on its ability to price risk for the whole economy, to determine companies’ values based on their likelihood of generating earnings. But traders are compensated on their quarterly or yearly performance, not on their distant foresight.

What is odd about many of these climate plays, which rely on such complex assumptions about the future, is how myopic they seem. They assume that the world will change around a stable, fixed point. American weather will curdle to such a degree that Tennessee will become an incubator for malaria, yet Wall Street banks and patent lawyers will saunter along as usual. Rising oceans will submerge coastal financial centers beneath several feet of saltwater, yet commodities markets will pay top dollar for Greenlandic uranium. Taken individually, these assumptions sound dubious. But as a whole, they mirror what’s happening on Wall Street. Each successive year incinerates the temperature figures of the previous one, yet the stock market continues to break records.

Climate Change Could Destroy His Home in Peru. So He Sued an Energy Company in Germany.

Categories: Climate Change, Decolonization, Energy, Environmental Justice, Humans & Nature

Increasing glacial melt is creating unstable, increasingly problematic glacial lakes, especially in the Andes and Himalaya Mountains. In Peru, Guardians are charged with watching these lakes to try to prevent a catastrophic flood.

Using similar methods that eventually were successful in bring lawsuits against Big Tobacco, vulnerable populations are trying to sue the large corporations that have overwhelming contributed to climate change. Surprisingly, just 90 companies are responsible for two-thirds of all the greenhouse gases emitted between 1751 and 2016. More than half those emissions have occurred since 1988. Still, it is an incredibly complex question to figure out the harm and recompense involved in large-scale, complex systems like earth’s climate.

Since 2017, eight United States cities, including New York and San Francisco, six counties, one state and the West Coast’s largest association of fishermen have brought suit against a host of corporations — Exxon Mobil, Royal Dutch Shell, BP, Chevron, Peabody Energy, among others — for selling products that caused the world to warm while misleading the public about the damage they knew would result.

Legal Rights for Lake Erie?

Categories: Humans & Nature

Across the world, governments are considering assigning legal rights to nature. Lake Erie is one of the first places this will be tested in the United States.

Environmentalism as Religion

Categories: Climate Change, Ecology, Humans & Nature

In this article, Joel Garreau explores the idea that environmentalism has become the new religion of choice for urban atheists, overtaking the traditional place of socialism for them.

In a widely quoted 2003 speech, Crichton outlined the ways that environmentalism “remaps” Judeo-Christian beliefs:

“There’s an initial Eden, a paradise, a state of grace and unity with nature, there’s a fall from grace into a state of pollution as a result of eating from the tree of knowledge, and as a result of our actions there is a judgment day coming for us all. We are all energy sinners, doomed to die, unless we seek salvation, which is now called sustainability. Sustainability is salvation in the church of the environment. Just as organic food is its communion, that pesticide-free wafer that the right people with the right beliefs, imbibe.”

According to Garreau, environmentalism has: 1) merged with Eastern-based spiritualism and concepts lifted from Hinduism, Daoism, or Buddhism; 2) harked back to pagan and animist traditional (pre-scientific) beliefs; and 3) and started a “greening” process of Judeo-Christian theology.

Freeman Dyson, the brilliant and contrarian octogenarian physicist, agrees. In a 2008 essay in the New York Review of Books, he described environmentalism as “a worldwide secular religion” that has “replaced socialism as the leading secular religion.” This religion holds “that we are stewards of the earth, that despoiling the planet with waste products of our luxurious living is a sin, and that the path of righteousness is to live as frugally as possible.” The ethics of this new religion, he continued,

“are being taught to children in kindergartens, schools, and colleges all over the world…. And the ethics of environmentalism are fundamentally sound. Scientists and economists can agree with Buddhist monks and Christian activists that ruthless destruction of natural habitats is evil and careful preservation of birds and butterflies is good. The worldwide community of environmentalists — most of whom are not scientists — holds the moral high ground, and is guiding human societies toward a hopeful future. Environmentalism, as a religion of hope and respect for nature, is here to stay. This is a religion that we can all share, whether or not we believe that global warming is harmful.”

Both Dyson and Garreau make a case that there is nothing wrong with the modern ecology movement and environmentalism being partially based on faith and belief and, like religion, looking partially beyond science and empiricism. But both of them warn that environmentalism could become a guilt-based Carbon Calvinism or turn to irrationalism. As Branden Allenby has written about the language of the carbon fundamentalists:

“indicates a shift from [seeking to help] the public and policymakers understand a complex issue, to demonizing disagreement. The data-driven and exploratory processes of science are choked off by inculcation of belief systems that rely on archetypal and emotive strength…. The authority of science is relied on not for factual enlightenment but as ideological foundation for authoritarian policy.”

The Senate Just Passed the Decade’s Biggest Public Lands Package

Categories: Ecology, Humans & Nature, Water

The 662-page measure, which passed 92 to 8, protects 1.3 million acres as wilderness, the nation’s most stringent protection, which prohibits even roads and motorized vehicles. It permanently withdraws more than 370,000 acres of land from mining around two national parks, including Yellowstone, and permanently authorizes a program to spend offshore-drilling revenue on conservation efforts.

The legislation establishes four new monuments, including the Mississippi home of civil rights activists Medgar and Myrlie Evers and the Mill Springs Battlefield in Kentucky, home to the decisive first Union victory in the Civil War.

The measure also expands the boundaries of more than a half-dozen national parks and adds three units, including two Civil War sites in Kentucky, the Mill Springs Battlefield and Camp Nelson. The package adds acreage to Death Valley and Joshua Tree national parks while protecting 350,000 acres of public lands between Mojave National Preserve and Death Valley, increasing the connectivity of the three sites.

The public lands package would also protect nearly 620 miles of rivers across seven states from damming and other development, often delegating management of the waterways to local authorities. It includes safeguards for a variety of rivers — everywhere from the tributaries for the wild Rogue River in Oregon, known for its vibrant salmon populations, to the once heavily polluted Nashua River that flows from Massachusetts to New Hampshire and is popular with kayakers.

The Tiny Swiss Company That Thinks It Can Help Stop Climate Change

Categories: Climate Change, Economics, Energy, Humans & Nature

Can two scientists from a Swiss firm called Climeworks perfect a novel process of “direct air capture” to remove CO2 from the atmosphere, bottle it, and store or sell it? Although Climeworks’s existing rooftop plant currently requires significant energy inputs to function, the two entrepreneurs (Christoph Gebald and Jan Wurzbacher) are finding ways to bring costs down and scale the size up. Right now they sell their expensive bottled CO2 to agriculture or beverage companies which seem willing to pay a premium for a vital ingredient they can use to help market their products as eco-friendly.

However, in the next seven years, Climeworks believes that it can bring expenses down to a level that would enable it to sell CO2 into more lucrative markets, like combining captured CO2 with hydrogen and fashioning many types of fossil-fuels. There is another company, Carbon Engineering, based in British Columbia, and backed by investors like Bill Gates, which is similarly seeking to produce synthetic fuel at large industrial plants from air-captured CO2. But eventually what Climeworks seeks to do once they lower costs and perfect the process is to pull vast amounts of CO2 out of the atmosphere and bury it, forever, deep underground, and sell that service as a carbon offset.

This fits Climework’s plan in a series of possible negative-emissions technologies (NETs), like planing new groves of trees, a process known as afforestation, which we can then burn for power generation, with the intention of capturing the power-plant emissions and pumping them underground, a process known as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, or BECCS. Other negative emissions technologies including manipulating farmland soil or coastal wetlands so they will trap more atmospheric carbon and grinding up mineral formations so they will absorb CO2 more readily, a process known as “enhanced weathering.” As it happens, the Climeworks machines on the rooftop do the work each year of about 36,000 trees.

Corn Tastes Better On The Honor System

Categories: Culture, Food, Humans & Nature, Top Picks

Robin Wall Kimmerer lays out the history of corn as an illustration of our relationship with the Earth and the way we live.

“My handful of Red Lake flint corn seeds were a gift from heritage seed savers, my friends at the Onondaga Nation farm, a few hills away. This variety is so old that it accompanied our Potawatomi people on the great migration from the East Coast to the Great Lakes. If you could carry only a single pouch of seeds, this would be the one to choose, with nutrition for physical health and teachings for spiritual health. Holding the seeds in the palm of my hand, I feel the memory of trust in the seed to care for the people, if we care for the seed. These kernels are a tangible link to history and identity and cultural continuity in the face of all the forces that sought to erase them. I sing to them before putting them into the soil and offer a prayer. The women who gave me these seeds make it a practice that every single seed in their care is touched by human hands. In harvesting, shelling, sorting, each one feels the tender regard of its partner, the human.

My neighbor bought his seeds from the distributor. They are a new GMO variety that he can’t save and replant but must buy every year. Unlike my seeds of many colors, his are uniform gold. They will be sown with the scent of diesel and the song of grinding gears. I suspect that those seeds have never been touched by a human, but only handled by machines. Nonetheless, when the seeds are in the ground and the gentle spring rain starts to fall, I suspect he looks up at the sky and prays. We both stand back and watch the miracle unfold.”

Listen to Robin Wall Kimmerer reading this article:

Initiation into a Living Planet

Categories: Decolonization, Humans & Nature

A key element of this transformation is from a geomechanical worldview to a Living Planet worldview. In my last essay, I argued that the climate crisis will not be solved by adjusting levels of atmospheric gases, as if we were tinkering with the air-fuel mixture of a diesel engine. Rather, a living Earth can only be healthy – can only stay living in fact – if its organs and tissues are vital. These comprise the forests, the soil, the wetlands, the coral reefs, the fish, the whales, the elephants, the seagrass meadows, the mangrove swamps, and all the rest of Earth’s systems and species. If we continue degrading and destroying them, then even if we cut emissions to zero overnight, Earth would still die a death of a million cuts.

That is because it is life that maintains the conditions for life, through dimly understood processes as complex as any living physiology. Vegetation produces volatile compounds that promote the formation of clouds that reflect sunlight. Megafauna transport nitrogen and phosphorus across continents and oceans to maintain the carbon cycle. Forests generate a “biotic pump” of persistent low pressure that brings rain to continental interiors and maintains atmospheric flow patterns. Whales bring nutrients up from the deep ocean to nourish plankton. Wolves control deer populations so that forest understory remains viable, allowing rainfall absorption and preventing droughts and fires. Beavers slow the progress of water from land to sea, buffering floods and modulating silt discharge into coastal waters so that life there can thrive. Mycelial mats tie vast areas together in a neural network exceeding the human brain in its complexity. And all of these processes interlock with each other.

Books

The Unlikely Peace at Cuchumaquic

Categories: Culture, Decolonization, Humans & Nature, Top Picks

The Unlikely Peace at Cuchumaquic is like one of the seeds Martín Prechtel describes—preserving a way of thought so endangered in the modern world. From the perspective of those growing up in the Western worldview, we need a translator in order to go below the surface of indigenous thought. Prechtel is an excellent guide on that journey, and he asks that you follow him outside of what you might consider normal in order to see something more wondrous and complex. This book is part story, part elegy to a culture under siege, and part how-to guide to resist the homogenizing and dulling forces that consume indigenous and earth-based culture, all written in a long, flowing prose that sweeps you up and away into the story.

“Turn that worthless lawn into a beautiful garden of food whose seeds are stories sown, whose foods are living origins. Grow a garden on the flat roof of your apartment building, raise bees on the roof of your garage, grow onions in the iris bed, plant fruit and nut trees that bear, don’t plant ‘ornamentals’, and for God’s sake don’t complain about the ripe fruit staining your carpet and your driveway; rip out the carpet, trade food to someone who raises sheep for wool, learn to weave carpets that can be washed, tear out your driveway, plant the nine kinds of sacred berries of your ancestors, raise chickens and feed them from your garden, use your fruit in the grandest of ways, grow grapevines, make dolmas, wine, invite your fascist neighbors over to feast, get to know their ancestral grief that made them prefer a narrow mind, start gardening together, turn both your griefs into food; instead of converting them, convert their garage into a wine, root, honey, and cheese cellar–who knows, peace might break out, but if not you still have all that beautiful food to feed the rest and the sense of humor the Holy gave you to know you’re not worthless because you can feed both the people and the Holy with your two little able fists.”

Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children From Nature-Deficit Disorder

Categories: Humans & Nature

“We have such a brief opportunity to pass on to our children our love for this Earth, and to tell our stories. These are the moments when the world is made whole. In my children’s memories, the adventures we’ve had together in nature will always exist.”

“”I had a place. There was a big waterfall and a creek on one side of it. I’d dug a big hole there, and sometimes I’d take a tent back there, or a blanket, and just lie down in the hole, and look up at the trees and sky. Sometimes I’d fall asleep back there. I just felt free; it was like my place, and I could do what I wanted, with nobody to stop me. I used to go down there almost every day.’

The young poet’s face flushed. Her voice thickened.

‘And then they just cut the woods down. It was like they cut down part of me.’”

Written in 2006, this book was about the declining amount of time that our children spent in nature, and the impact it was having on their wellbeing. The most powerful part are the interviews with children about their relationships with the natural world.

It’s a poignant read in the age of the smartphone.

The Burning Season: The Murder of Chico Mendes and the Fight for the Amazon Rain Forest

Categories: Ecology, Humans & Nature

“It became clear that the murder was a microcosm of the larger crime: the unbridled destruction of the last great reservoir of biological diversity on Earth.”

Chico Mendes was a rubber tapper in the Brazilian state of Acre in the remote Amazon Basin. He became a community organizer and successful environmental activist, advocating for reserves of forest where rubber could be grown in agro-forestry practices. He was murdered for his audacity to stand up against the largest forces on earth to ask for the preservation of the Amazon.

The Final Forest: The Battle for the Last Great Trees of the Pacific Northwest

Categories: Ecology, Humans & Nature

The old-growth trees of America’s Pacific Northwest are the largest in the world. To walk in those forests leaves you speechless at the scale of the natural world. Yet, over 90% of those forests have already been destroyed by logging. This is the story of logging and extraction in those forests, the people who earn their living from the land, the people who spent their lives fighting to save the forests, and the spotted owl that was at the center of the legal decision that brought down the logging industry in the early 1990’s. We hear from remarkably different perspectives about how they want to live in a landscape that they all love.

Collapse

Categories: Climate Change, Ecology, Economics, Humans & Nature

What happens when a society outstrips its natural resources? Jared Diamond, legendary author of Guns, Germs, and Steel, takes a sweeping tour of the world to visit the societies that have collapsed in the distant past from Chaco Canyon to Easter Island to Greenland, and into recent times with the Rwandan genocide. He then analyzes our current state of resource overconsumption in a globalized world. As always, Diamond is incredibly detailed, with insights that cut through the fog of confusion that surrounds our modern predicament.

“Two types of choices seem to me to have been crucial in tipping the outcomes [of the various societies’ histories] towards success or failure: long-term planning and willingness to reconsider core values. On reflection we can also recognize the crucial role of these same two choices for the outcomes of our individual lives.”

“I have often asked myself, “What did the Easter Islander who cut down the last palm tree say while he was doing it?” Like modern loggers, did he shout “Jobs, not trees!”? Or: “Technology will solve our problems, never fear, we’ll find a substitute for wood”? Or: “We don’t have proof that there aren’t palms somewhere else on Easter, we need more research, your proposed ban on logging is premature and driven by fear-mongering”? Similar questions arise for every society that has inadvertently damaged its environment.”

Encounters With The Archdruid

Categories: Humans & Nature, Top Picks

“Sooner or later in every talk, Brower describes the creation of the world. He invites his listeners to consider the six days of Genesis as a figure of speech for what has in fact been four billion years. On this scale, a day equals something like six hundred and sixty-six million years, and thus ‘all day Monday and until Tuesday noon, creation was busy getting the earth going.’ Life began Tuesday noon, and ‘the beautiful, organic wholeness of it’ developed over the next four days. ‘At 4 P.M. Saturday, the big reptiles came on. Five hours later, when the redwoods appeared, there were no more big reptiles. At three minutes before midnight, man appeared. At one-fourth of a second before midnight, Christ arrived. At one-fortieth of a second before midnight, the Industrial Revolution began. We are surrounded with people who think that what we have been doing for the last one-fortieth of a second can go on indefinitely. They are considered normal, but they are stark, raving mad.”

David Brower was a giant in environmental protection in the United States. As president of the Sierra Club, he grew the organization from a small mountaineering club to the largest environmental lobbying group in the world: over 3.5 million members. Many credit Brower for the preservation of the Grand Canyon and the North Cascades. In this book, John McPhee follows Brower for three encounters with his rivals: a mining geologist, a real estate developer, and a dam builder.

The One-Straw Revolution

Categories: Culture, Food, Humans & Nature

“Human beings are the only animals who have to work, and I think that is the most ridiculous thing in the world. Other animals make their livings by living, but people work like crazy, thinking that they have to in order to stay alive. The bigger the job, the greater the challenge, the more wonderful they think it is. It would be good to give up that way of thinking and live an easy, comfortable life with plenty of free time. I think that the way animals live in the tropics, stepping outside in the morning and evening to see if there is something to eat, and taking a long nap in the afternoon, must be a wonderful life. For human beings, a life of such simplicity would be possible if one worked to produce directly his daily necessities. In such a life, work is not work as people generally think of it, but simply doing what needs to be done.”

“When it is understood that one loses joy and happiness in the attempt to possess them, the essence of natural farming will be realized. The ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops, but the cultivation and perfection of human beings.”

Fukuoka is hailed across the world as a master in organic agriculture. His methods of “do-nothing farming” have inspired many, and his questions undermine all assumptions about what it takes to feed ourselves in the industrial age. Part Zen treatise, part memoir, part farming guide, this book is a classic, and a must-read for anybody who grows their own food (which should be everybody).

Braiding Sweetgrass

Categories: Decolonization, Ecology, Humans & Nature, Top Picks

“On Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at 9:35 a.m., I am usually in a lecture hall at the university, expounding about botany and ecology—trying, in short, to explain to my students how Skywoman’s gardens, known by some as “global ecosystems,” function. One otherwise unremarkable morning I gave the students in my General Ecology class a survey. Among other things, they were asked to rate their understanding of the negative interactions between humans and the environment. Nearly every one of the two hundred students said confidently that humans and nature are a bad mix. These were third-year students who had selected a career in environmental protection, so the response was, in a way, not very surprising. They were well schooled in the mechanics of climate change, toxins in the land and water, and the crisis of habitat loss. Later in the survey, they were asked to rate their knowledge of positive interactions between people and land. The median response was “none.”

I was stunned. How is it possible that in twenty years of education they cannot think of any beneficial relationships between people and the environment? Perhaps the negative examples they see every day— brownfields, factory farms, suburban sprawl—truncated their ability to see some good between humans and the earth. As the land becomes impoverished, so too does the scope of their vision.”

Braiding Sweetgrass is a beautiful journey through our personal and cultural relationships with the natural world. Robin Wall Kimmerer writes from the dual perspectives of a Native American woman and an ecology professor, outlining the intersection between science and traditional ways of knowing the Earth. She writes to share a vision—how we can begin to form beneficial relationships with the natural world and move beyond a model of damage control.

The Man Who Planted Trees

Categories: Culture, Ecology, Humans & Nature, Top Picks

“The oaks of 1910 were then ten years old and taller than either of us. It was an impressive spectacle. I was literally speechless and, as he did not talk, we spent, the whole day walking in silence through his forest. In three sections, it measured eleven kilometers in length and three kilometers at its greatest width. When you remembered that all this had sprung from the hands and the soul of this one man, without technical resources, you understand that men could be as effectual as God in other realms than that of destruction.”

This gem is among our favorite stories: a simple allegory about the efforts of one man to change the world around him. It’s wonderfully written and just a fifteen minute read. This version, the story read aloud over an animated illustration, won an academy award for short films in 1987, and we highly recommend it. You can find Jeff’s transcription of this version here.

The Unsettling of America

Categories: Culture, Economics, Food, Humans & Nature, Top Picks

“We have given up the understanding — dropped it out of our language and so out of our thought — that we and our country create one another, depend on one another, are literally part of one another; that our land passes in and out of our bodies just as our bodies pass in and out of our land; that as we and our land are part of one another, so all who are living as neighbors here, human and plant and animal, are part of one another, and so cannot possibly flourish alone; that, therefore, our culture must be our response to our place, our culture and our place are images of each other and inseparable from each other, and so neither can be better than they other.”

Wendell Berry is a farmer and poet, outraged at what is happening with the spread of industrial agriculture. He details how our connection to the land is the definition of our culture, and how our industrial culture is killing both itself and the planet. If you read just one book about food, this should be it. Written over 50 years ago, Berry’s insight is still urgent and could have been written yesterday.

The Great Thirst: Californians and Water: A History

Categories: Humans & Nature, Water

“[The Spanish and Mexican] attitude toward water changed after the discovery of gold, when thousands poured into California imbued with a spirited individualism and an appetite for a profit that elevated the exploitation of nature to new heights, set the stage for a system of private monopolization of land and water that has persisted into modern times, transformed political and legal institutions, and prompted California’s emergence as the nation’s preeminent water seeker—or, to be more precise and as emphasized in this account, California’s emergence as a collection of water seekers.”

Hundley untangles the dense, confusing knot of California’s water propertization, regulatory systems, and their underlying values to form a coherent, comprehensive history (1770’s-1990’s) tracing the management and use of water by, and accompanying interests of, aboriginal Americans, hispanic settlers, Gold Rush settlers, and contemporary “water seekers.” From the publisher: “The desire to use, profit from, manipulate, and control water drives the people and events in this fascinating narrative until, by the end of the twentieth century, a large, colorful cast of characters and communities has wheeled and dealed, built, diverted, and connived its way to an entirely different statewide waterscape.”

A River Lost: The Life and Death of the Columbia

Categories: Humans & Nature, Water

“This book is about the destruction of the great river of the West by well-intentioned Americans whose lives embodied a pernicious contradiction. They prided themselves on self-reliance, yet depended on subsidies. They distrusted the federal government, yet allowed it to do as it pleased with the river and the land through which it flowed. As long as there was federal money, they did not mind that farmers wasted water, that dams pushed salmon to extinction, or that plutonium workers recklessly spilled radioactive gunk beside the river…..My story of the river is a memoir, a history, and a lament for a splendid corner of the American West that maimed itself for the sake of prosperity and that continues not to understand why.”

The Columbia river in the American West has been dammed and polluted to death, reduced to a piece of computer-controlled power-generating machinery, while the people and animals that lived off and in it were denied access or decimated. All that’s left of the Columbia is “puddled remains,” history, and memories, which Harden recounts as he travels along the scene, and victim, of crime. Harden laments not only both the death of the wild river but also the death of the conscience of the American public, who did not hold federal government and farming, electricity, shipping, timber, and nuclear industries accountable for exploiting the Columbia. It’s noteworthy that Harden does a great job talking to people with various interests and stakes in the Columbia and understanding where they (or their industry) is coming from, thus avoiding dehumanizing them or perpetuating a battleground narrative.

The Earth Is Enough: Growing Up in a World of Flyfishing, Trout & Old Men

Categories: Humans & Nature

“The land was theirs, free and clear, and they had evidently made a decision decades before to keep it the way it was, to work with it rather than against it. A decision for trout and quail instead of beans. It seemed to them the world had too many beans and too few trout and wild turkeys. Their life in the mountains became a compromise, a balance of giving and taking.”

In 1956, Middleton, at 14 years of age, was placed under the care of his grandfather and his great-uncle and their Sioux neighbor on their farm in the Ozark Mountains in north Arkansas. Under their tutelage, he gets an education in fly-fishing, 19th-century farming, and simple living, and most importantly, a respect for the wild earth. It’s a pleasure to get to know the eccentric and wise characters of Middleton’s boyhood, and the place they are loyally devoted to.

Arctic Dreams

Categories: Humans & Nature

“No culture has yet solved the dilemma each has faced with the growth of a conscious mind: how to live a moral and compassionate existence when one is fully aware of the blood, the horror inherent in all life, when one finds darkness not only in one’s own culture but within oneself.”

“What does it mean to grow rich?

Is it to have red-blooded adventures and to make a ‘fortune,’ which is what brought the whalers and other entrepreneurs north?

Or is it, rather, to have a good family life and to be imbued with a far-reaching and intimate knowledge of one’s homeland, which is what the Tununirmiut told the whalers at Pond’s Bay wealth was?

Is it to retain a capacity for awe and astonishment in our lives, to continue to hunger after what is genuine and worthy? Is it to live at moral peace with the universe?”

In his National Book Award-winning book, Lopez shows the reader how wealthy he is in the latter category. Here is a man who is truly in touch with where he is—the Arctic—culturally, historically, scientifically, emotionally, and spiritually. He meticulously and reverentially examines the Far North from every angle, studying how a place can gets under our skin and inform our own human nature.

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

Categories: Humans & Nature

“The answer must be, I think, that beauty and grace are performed whether or not we will or sense them. The least we can do is try to be there.”

“I am no scientist. I explore the neighborhood…It is my leisure as well as my work, a game…I walk out; I see something, some event that would otherwise have been utterly missed and lost; or something sees me, some enormous power brushes me with its clean wing, and I resound like a beaten bell.”

In this Pulitzer-prize winning book, Dillard takes us with her on her explorations throughout the Tinker Creek valley in Virginia’s Blue Ridge range over the course of a year’s seasons. She writes lucidly about her engagements with her environment and the variety of beings within it, as well as meditations on presence, transience, mortality, fertility, perception, and the divine. It’s a treat to spend time with someone who knows where they live so well, and who can tell you about it with such strikingly visionary writing.

The Island Within

Categories: Humans & Nature

“I’ve often thought of the forest as a living cathedral, but this might diminish what it truly is. If I have understood Koyukon teachings, the forest is not merely an expression or representation of sacredness, nor a place to invoke the sacred; the forest is sacredness itself.”

“[I breathe in the] air that has passed continually through life on earth…pass it on, share it in equal measure with billions of other living things, endlessly, infinitely.”

In essays spanning the course of a hunter’s year, Nelson, an anthropologist who studies indigenous cultures of Alaska, describes his attempt to live off the land on an island off of the coast of southeast Alaska and forge a deeper relationship to both its minute parts—puffins, otters, whales—and its dazzling, sacred whole. He writes beautifully about “[claiming]” and “being claimed by” the island, a “place that wholly engages the heart and mind.”

Tom Brown’s Field Guide to Nature Observation and Tracking

Categories: Humans & Nature

“This earth is a garden, this life a banquet, and it’s time we realized that it was given to all life, animal and man, to enjoy.”

Drawing on his childhood lessons on tracking, survival skills, and spirituality from a Lipan Apache elder and his experiences finding fugitives and missing persons, Brown teaches readers how to restore and develop our five senses to enter into a deeper relationship with nature, and how to track animals (including humans). Includes illustrations by Heather Bolyn.

Wilderness and the American Mind: Fifth Edition

Categories: Culture, Humans & Nature

“Wilderness is a state of mind…not so much what wilderness is but what men think it is.”

Through history, politics, economics, and philosophy Nash captures (primarily white male city-dwelling) Americans’ relationship to nature in the United States of America since the country’s founding through the modern day. It traces the history of the environmental conservation/preservation movement and how we’ve come from fearing an overwhelming wilderness to now regarding it as a scarce national commodity and intellectual (and spiritual) concept. Though the perspective is narrowly focused and the writing sometimes academic to the point of dryness, it’s been described as “the Book of Genesis for conservationists” for a good reason: it’s possibly the best overview of American environmental history and represents a career’s worth of study, updated through five editions.

The Snow Leopard

Categories: Humans & Nature

“The secret of the mountain is that the mountains simply exist, as I do myself: the mountains exist simply, which I do not. The mountains have no “meaning,” they are meaning; the mountains are. The sun is round. I ring with life, and the mountains ring, and when I can hear it, there is a ringing that we share. I understand all this, not in my mind but in my heart, knowing how meaningless it is to try to capture what cannot be expressed, knowing that mere words will remain when I read it all again, another day.”

In the winter of 1973, Mathhiessen accompanied his field biologist friend George Schaller on a five-week expedition and spiritual pilgrimage in Nepal’s Himalayan mountains to study blue sheep, though he was more interested in catching a glimpse of the sheep’s predator: the elusive, mystical snow leopard. Mathhiessen writes precisely and beautifully (though a bit densely) about Zen and Tibetan Buddhist teachings, especially emptiness, impermanence, and acceptance, as he finds a way through his grief for his late wife. (The Snow Leopard won the National Book Award in two categories 1979 and 1980.)

The Practice of the Wild

Categories: Culture, Humans & Nature

Read here

“I hope to investigate the meaning of wild and how it connects with free and what one would want to do with these meanings. To be truly free one must take on the basic conditions as they are—painful, impermanent, open, imperfect—and then be grateful for impermanence and the freedom it grants us. For in a fixed universe there would be no freedom. With that freedom we improve the campsite, teach children, oust tyrants. The world is nature, and in the long run inevitably wild, because the wild, as the process and essence of nature, is also an ordering of impermanence.”

“Nature is not a place to visit, it is home—and within that home territory there are more familiar and less familiar places. Often there are areas that are difficult and remote, but all are known and even named.”

In nine essays, the poet, environmentalist, and social critic Gary Snyder, described as “the laureate of Deep Ecology,” draws on his understanding of Zen Buddhist & Daoist teachings, Native American mythology, and his personal relationships to place as a logger and conservationist to interrogate what wildness really means how we can recognize and restore it in the world and in ourselves. But primarily, this is not a book about environmental activism; it is a book asking what it means to be human in a world that is rapidly changing. Where the wild used to mean home and source of life, it now means playground and escape.

Into the Wild

Categories: Humans & Nature

“So many people live within unhappy circumstances and yet will not take the initiative to change their situation because they are conditioned to a life of security, conformity, and conservation, all of which may appear to give one peace of mind, but in reality nothing is more damaging to the adventurous spirit within a man than a secure future. The very basic core of a man’s living spirit is his passion for adventure.”

“You are wrong if you think Joy emanates only or principally from human relationships. God has placed it all around us. It is in everything and anything we might experience. We just have to have the courage to turn against our habitual lifestyle and engage in unconventional living.”

“Mountains make poor receptacles for dreams.”

In the spirit of London, Muir, and Thoreau, in 1992 an idealistic college graduate, Chris McCandless, left behind his home, family, belongings, and money—society as he knew it—to “wallow in the raw, unfiltered experiences” of the Alaskan wilderness. At first his odyssey seems inspiring and righteous. But then he dies, a mere four months after he left home. Krakauer (author of Into Thin Air about an Everest expedition gone horribly wrong) describes McCandless’ story and lets us decide: was McCandless a philosopher rejecting the ills of materialistic society to live a more meaningful life, becoming a martyr in the process? Or merely an inconsiderate and ill-prepared young man, the tragic victim in a cautionary tale against stubborn independence and idealism to the point of delusion?

A Sand County Almanac

Categories: Culture, Ecology, Humans & Nature

“Cease being intimidated by the argument that a right action is impossible because it does not yield maximum profits, or that a wrong action is to be condoned because it pays.”

“Conservation is getting nowhere because it is incomprehensible with our Abrahamic concept of land. We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect. There is no other way for land to survive the impact of the mechanized man, nor for us to reap from it the esthetic harvest it is capable, under science, of contributing to culture. That land is a community is the basic concept of ecology, but that land is to be loved and respected is an extension of ethics. That land yields a cultural harvest is a fact long known, but latterly often forgotten…perhaps such a shift of values can be achieved by reappraising things unnatural, tame and confined in terms of things natural, wild, and free.”

In a series of essays in three parts, Leopold describes the “delights and dilemmas of one who cannot [live without wild things].” As a part-time farmer who works to make a home out of of an overexploited and abandoned farm in Sand County, Wisconsin, he is intimate with those delights and dilemmas. In part one, he sharply, lovingly observes the farm and its minute changes throughout the seasons: from the geese he admires to the partridge he hunts. In part two, he describes conservation issues affecting a variety of places scattered throughout North America. In part three, he expresses his grief at America’s current (at the time of writing) relationship with nature and what might be done to restore a healthy, compassionate relationship and land ethic. Throughout the book are lovely illustrations drawn by Charles W. Schultz.

The Abstract Wild

Categories: Culture, Economics, Humans & Nature, Top Picks

“Those early visits to the Maze, Glen Canyon, and the Escalante led me to the margins of the modern world, areas wild in the sense Thoreau meant when he said that in wildness is the preservation of the world: places where the land, the flora and fauna, the people, their culture, their language and arts were still ordered by energies and interests fundamentally their own, not by the homogenization and normalization of modern life.”

“[Wildness is] the relation of free, self-willed, and self-determinate ‘things’ with the harmonious order of the cosmos.”

“Something vast and old is vanishing and our rage should mirror that loss.”

In a collection of eight essays, Turner examines the questions: “how wild is wilderness and how wild are our experiences in it?” He argues—angrily, unapologetically—that the threats to wilderness have their root in six harmful abstract values and mindsets that shape our modern character and culture: 1) “our diminished personal experience of nature,” 2) “our preference for artifice,” 3) “our…dependence on experts to control and manipulate a natural world we no longer know,” 4) “our addiction to economics, recreation, and amusement at the expense of other values,” 5) a Western homogeneity and monoculture of biology, culture, language, thought, and social structures, and 6) an ignorance of or refusal to recognize the catastrophic loss of our “several-million-year-old intimacy with the natural world.” He calls for a change in character and in culture so we can reunited with the “life-force,” reborn as champions who confront the abstractions that keep the wild abstract from us.

Walden

Categories: Humans & Nature

“The cost of a thing is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.”

“Live in each season as it passes; breathe the air, drink the drink, taste the fruit, and resign yourself to the influence of the earth.”

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.”

What would happen if you left your (sub)urban life as you knew it to live in the woods? Walden Pond is one man’s answer. In the mid 1800’s American Transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau undertook an experiment to live for two years, two months, and two days as simply and self-sufficiently as possible in a cabin in the woods by Walden Pond outside of Concord, Massachusetts. He looks both outward and inward as he details and opines on his natural surroundings, farm and maintenance work, society, spirituality, literature, and human nature.

The Only Kayak

Categories: Humans & Nature

“Wilderness areas are places to explore deeply yet lightly; to exercise freedom but also restraint, to manage but also leave alone, to bring us face-to-face with a dilemma in our democracy. How do we convince people to save something they may never see, touch, or hear? A starving man can’t eat his illusions, let alone his principles.”

“I live in the sunlight of friends and the shadows of glaciers.” So begins Kim Heacox’s weave of memoir, history, and conservation treatise on living in Glacier Bay, Alaska, a place where the myth of the “Last Frontier” still feels alive. His love for Glacier Bay, Alaska, was first ignited when he worked there as a park ranger in the late 1970’s, and developed as he built a life there over the next 25-odd years. He becomes determined to conserve such wilderness, and wrestles with the paradoxes of loving a place that is rapidly disappearing, and sharing that love when recreating there seems to make Glacier Bay more vulnerable to overdevelopment. With humor and thoughtfulness Heacox captures the spectrum of relationships we have to nature and with each other.

Desert Solitaire

Categories: Humans & Nature

“Wilderness. The word itself is music.”

“A man could be a lover and defender of the wilderness without ever in his lifetime leaving the boundaries of asphalt, powerlines, and right-angled surfaces. We need wilderness whether or not we ever set foot in it. We need a refuge even though we may never need to set foot in it. We need the possibility of escape as surely as we need hope; without it the life of the cities would drive all men into crime or drugs or psychoanalysis.”

In Desert Solitaire Edward Abbey, the author of the iconic novel The Monkey Wrench Gang (about the shenanigans of anarchist environmentalists as they battle industrial development) reflects on his time as a ranger throughout three seasons in Arches National Park in southeastern Utah. With a writing voice that’s both beautiful and fiery in turns, he details the hardships and rewards of living in “nature in its purest form.” Desert Solitaire is also an impassioned call to nature-lovers to protect such places from being exploited by oil, mining, and tourism industries.

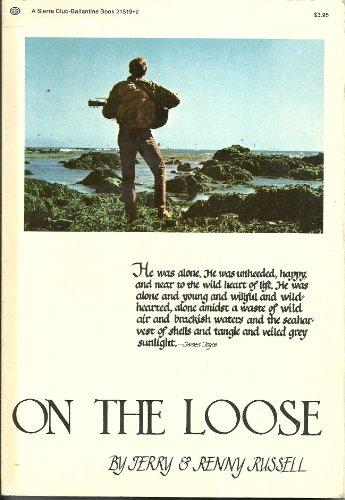

On The Loose

Categories: Humans & Nature

“We live in a house that God built but that the former tenants remodelled–blew up, it looks like–before we arrived. Poking through the rubble in our odd hours, we’ve found the corners that were spared and have hidden in them as much as we could. Not to escape from but to escape to: not to forget but to remember.”

“It feels good to say ‘I know the Sierra’ or ‘I know Point Reyes.’ But of course you don’t—what you know better is yourself, and Point Reyes and the Sierra have helped.”

On The Loose is a memoir that recounts the adventures of authors Renny and his brother Terry as they journey together throughout the American West in the 1950s and ‘60s. An inspiring book about how self-knowledge can be gained through exploring and revering wild places in the precious time before they are destroyed. (Fun fact: Terry was 21 and Renny was 19 when they wrote the book.) It also includes original photographs from their travels through famous wilderness areas such as Yosemite and Glen Canyon.